Ordinary Families, Extraordinary Lives: Assets and Poverty Reduction in Guayaquil 1978-2004 (Caroline Moser)

Submitted by frankie on Fri, 2010-03-19 09:45.

Caroline Moser

From: ‘The Guardian’, London, Tuesday 2 March 2010

Studying life in Ecuador

A review article by Chris Arnot

One academic has spent 30 years following – and sharing – the life of a poor community in Ecuador.

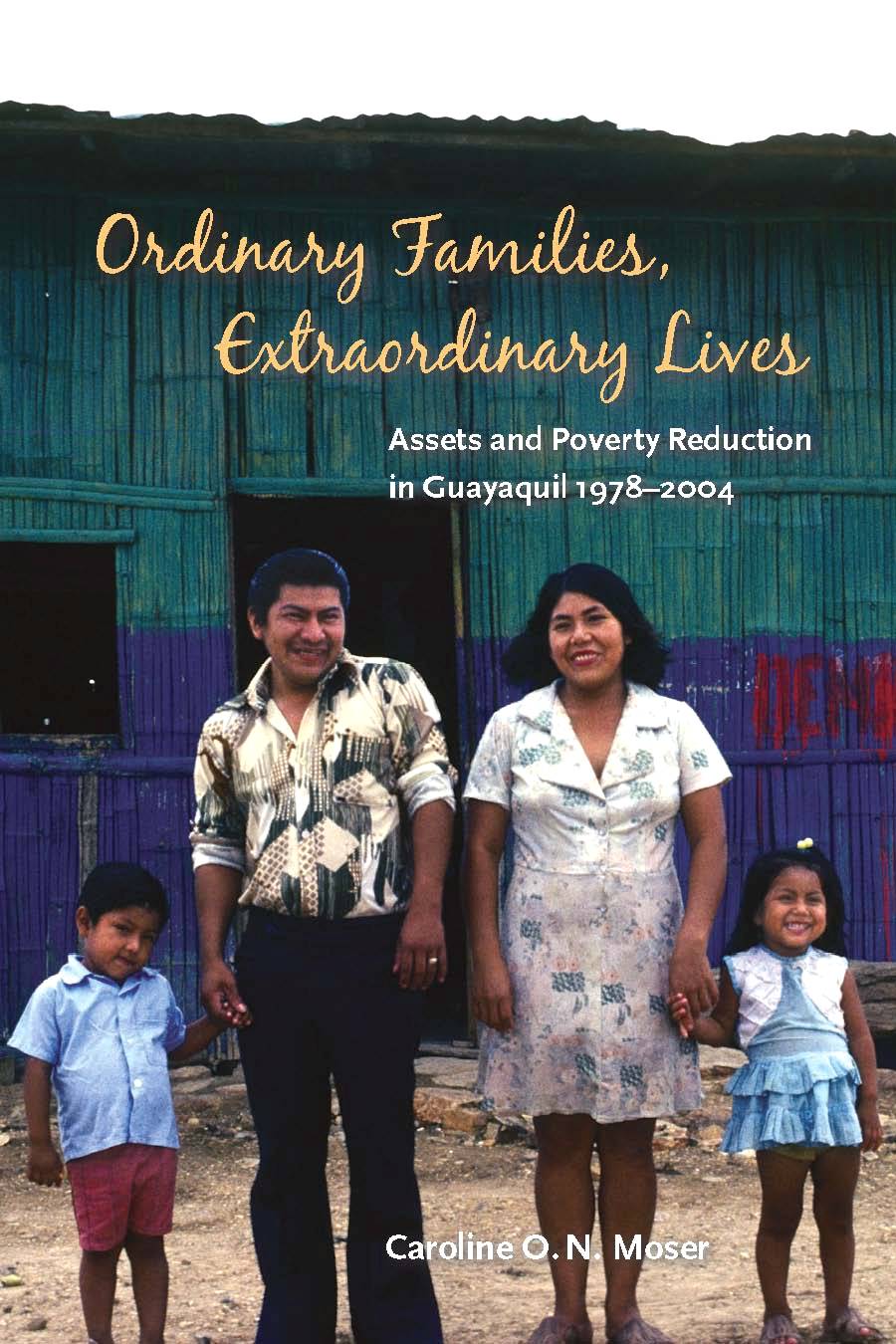

Caroline Moser with her family and local people in Guayaquil, Ecuador, in 1973.

ORDINARY FAMILIES, EXTRAORDINARY LIVES

Prologue

The views expressed in 'Recent News & Reflections' are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any of the governments, organisations or agencies with whom they have been working.

Caroline Moser has published reflections and analysis of a quarter of a century’s longitudinal research on the struggle out of poverty of three generations of families’ who started life squatting over tidal mangrove swamps in Guayaquil, Ecuador. [A review article from ‘The Guardian’ (UK national newspaper) and extract from the book’s Prologue].

|

Life over a waterlogged mangrove swamp on the edge of the Ecuadorian city of Guayaquil was tough in 1978, but it didn't stop anthropologist Professor Caroline Moser going to live there for eight and a half months with her husband and two children, who were taken out of their Church of England primary school in south London, aged eight and six, and put into a class of 70.

It was to be the first of many visits to Guayaquil, as Moser, then attached to the Development Planning Unit (DPU) at University College London, and now Director of Manchester University's Global Urban Research Centre, was to chart the development of the community over a period of nearly 30 years.

And the recently published result of her relationship with the community is her book Ordinary Families, Extraordinary Lives*, a study of everyday life in a Latin American community over three decades. The subtitle is Assets and Poverty Reduction in Guayaquil, 1978-2004.

Over that period, Moser returned to the slum settlement of Indio Guayas 10 times and each time stayed for at least a month. Unlike some anthropologists, she didn't want to drop in and "extract information" in the way that multinational companies extract oil from Ecuador. She wanted to live alongside the 244 households that she studied in depth, to make friends and share their experiences. "I have a passion for development work," she says, "and that informs everything I do."

In the initial long trip, her children found school, where they learned by rote, very different from England. Like the other buildings in Indio Guayas, the school was bamboo with a corrugated iron roof. The houses were connected by precarious catwalks on stilts. Amoebic dysentery was rife. Residents had to fill up petrol drums with fresh water from a visiting tanker. "We washed in a plastic container and shared the contents in a particularly hot and sticky climate," says Moser.

Her husband, Brian Moser, worked for Granada Television and had a distinguished pedigree making films about tribes in remote parts of the world. His wife is more concerned with urban communities. "I'd done my PhD on market traders in Bogota, and I've since worked on drug-related violence in Jamaica and Guatemala," she says. "Brian and I wanted to use the model of Disappearing World [his TV documentary series about vanishing tribes] in an urban context, blending anthropology with skilled camera work."

The film was eventually made for Central Television under the title People of the Barrio (neighbourhood). Moser's book would take considerably longer to appear – and for good reason. She wanted to take a long-term perspective, albeit at close quarters.

Ordinary Families, Extraordinary Lives is dedicated to Emma Torres, a young community leader in Guayaquil in 1978, who became a close friend. She saw the benefit of publicity and acted as a bridge between her neighbours and the incomers from the UK. "She also taught me how to cook using kerosene," recalls Moser, who still stays with the Torres family when she returns to Indio Guayas. Instead of a bamboo hut, they now live in a house made of cement blocks, as do most of their neighbours. They have electricity, sanitation and running water.

"Materially, these families are a lot better off than they were in the 70s," says Moser. "Ecuador's transition from military dictatorship to democracy meant that politicians were prepared to offer improvements in their lifestyle in return for votes. Schooling has improved as well. That, in turn, has led to higher aspirations." When these are not met, alienation can set in. "The downside is the lack of employment opportunities alongside drug-related crime. For young men there would appear to be three options – hang on and work their butts off for little money; join a gang and get involved in drugs and robbery; or emigrate."

With the help of Torres's daughter, Lucy, Moser has tracked down some of the emigrants to their new lives in Barcelona. She is currently seeking funding for an in-depth comparative study. "Some of them have taken out dodgy mortgages on apartments and I want to see how the collapse of the sub-prime market has affected them," she says. "Until the recession, some of them were doing quite well. I compared the incomes of two brothers doing similar factory work. The one in Guayaquil is earning $62 a month and the one in Barcelona the equivalent of $820. But he's also sending remittance money to his family back home."

And the trauma of being transplanted from a CofE primary in the first world to a slum school in the third world did not affect her two sons long term. One of them is now an economist, working in Russia; the other is a social development worker for Shell. "I think the experience of living on the edge of Guayaquil sold him for life on issues of development," she says.

* Ordinary Families, Extraordinary Lives is published by Brookings Press of Washington DC at £23.90

|

Table of Contents

Prologue (see below)

Chapters:

1. Introduction to Indio Guayas and the Study

2. Grappling with Poverty: From Asset Vulnerability to Asset Accumulation

3. A Home of One’s Own: Squatter Housing as a Physical Asset

4. Social Capital, Gender, and the Politics of Physical Infrastructure

5. Leadership, Empowerment, and “Community Participation” in Negotiating for Social Services

6. Earning a Living or Getting By: Labor as an Asset

7. Families and Household Social Capital: Reducing Vulnerability and Accumulating Assets

8. The Impact of Intrahousehold Dynamics on Asset Vulnerability and Accumulation

9. Daughters and Sons: Intergenerational Asset Accumulation

10. Migration to Barcelona and Transnational Asset Accumulation

11. Youth Crime, Gangs, and Violent Death: Community Responses to Insecurity

12. Research and Policy Lessons from Indio Guayas

Appendixes:

A. Research Methodology: Guayaquil Fieldwork

B. Guayaquil’s Political and Economic Context

C. Econometric Methodology

Notes

References

Index

“Most people have come here because they are in the same state as me. I have two children, but many have five, six, up to eight children. Salaries are so low they don’t cover food, let alone rent. We are all poor; you cannot describe it any other way. Anyone who has money would not come here; only those who are poor and really in need.” — Marta

With these words Marta, leader of the local community committee, introduced me to her neighbors in Indio Guayas in 1978. These were poor households—only one in five lived above the poverty line—squatting in bamboo-walled houses in a mangrove swamp on the periphery of Guayaquil, Ecuador. Recently arrived, they were young, upwardly aspiring families who had taken advantage of free waterlogged land to build and own their homes and were living without basic services such as electricity, running water, or plumbing, or social services such as health care and education. Yet thirty years later Indio Guayas was a consolidated settlement with reduced levels of poverty and less than one in three households considered poor.

This book describes how households living in this typical third world urban slum community relentlessly and systematically struggled to get out of poverty while simultaneously contesting with the authorities to provide both physical and social infrastructure. Over a thirty-year period, households spanning two generations steadily built up “portfolios” of assets, accumulating human, social, financial, and physical capital, with their day-to-day struggles involving success stories as well as tragic disasters and failures. Such documentation of the minutiae of daily slum reality lacks the immediacy of sensational drama that instant global communication increasingly demands. However, while tabloid stories may relieve our daily monotony, they poorly approximate reality. Behind the mundane slum routine of ordinary families lie extraordinary lives. The challenge is to portray the amazing fortitude and determination of people who have not only survived but quietly brought up their children; relentlessly striven to prosper in the adverse conditions of an urban slum, a fluctuating economy, and a crisis-ridden government; and tried to give the next generation better opportunities in the far more complex world of the twenty-first century.

This prologue briefly introduces the main themes running through this book and outlines the structure of its contents. The first theme is the issue of poverty itself, with its reduction being one of the most relentless development challenges of the past fifty years, as highlighted by global poverty reports (World Bank 1990, 2000) and the UN Millennium Development Goals (United Nations General Assembly 2001). It is this changing debate on the nature, measurement, and contextualization of poverty that informs the book.

What do we mean by poverty? Robert Chambers maintains that poverty often becomes “what has been measured and is available for analysis” (2007, p. 18). He argues that by focusing only on readily available data, development analysts have often constructed a flawed conceptualization of poverty that ignores information not easily gathered and quantified. Equally, such analyses fail to include interpretations of poverty, deprivation, and exclusion grounded in the agency and identity of the poor themselves.

This book addresses such limitations by going beyond the measurements of income or consumption poverty to introduce as a central focus an asset accumulation framework. This identifies the range of assets that households, and individuals within them, accumulate, consolidate, or at times lose through their erosion. At the same time, it is important to recognize that while the measurement of assets can help identify overall asset accumulation trends, it cannot provide explanations of the underlying social, economic, and political processes within which such accumulation occurs. To identify how and when different assets are accumulated, this book, of necessity, broadens the focus to tell the story not only through statistics and numbers but also through the lives of individuals and families. This requires an understanding of the social relations within families, households, and communities as well as their structural relationships with external actors (see Harriss 2007a).

A second theme relates the contrast between short-term static “snapshots” and longitudinal studies of poverty. Snapshots can only capture a single point in time. Poverty, however, is dynamic and constantly changes along with both internal life cycles and external circumstances, such as natural disasters, government policy, and social forces. The longitudinal study presented here provides the opportunity to go beyond a short-term diagnostic of poverty levels or asset portfolios to document longer-term factors. It identifies the agility of individuals and households in detecting opportunities and taking advantage of them when responding to changing macroeconomic conditions—whether it is the Ecuadorian structural adjustment programs of the 1980s or the globalization-linked dollarization of the late 1990s. A longitudinal study not only incorporates changes in poverty levels and asset portfolios but also includes the evolution of subjective perceptions of well-being, including intergenerational differences. In the case of mothers and daughters, these relate to changes in gender power relations and perceptions of empowerment; from the perspective of fathers and sons, it includes the positive upward mobility expectations of less-educated fathers versus the rising aspirations and growing despair of their better-educated sons.

This book tells the story of how poor households struggled to get out of poverty and accumulated assets. Just as Oscar Lewis focused on a single day in the lives of five families when he conceptualized poor households as living in a “culture of poverty” in urban Mexico in the 1960s and 1970s (Lewis 1966; Lewis and others 1975), so too the present narrative about Indio Guayas is focused through the voices of five women and their families, but in this case over a thirty-year period. This highlights a third theme that relates to the agency of individuals—community members and leaders alike—in achieving such outcomes. Associated with this is their contestation and negotiation with the range of state, civil society, and international agencies that assist, rather than effect, poverty reduction or community consolidation. In a context of changing delivery systems, the sequence of priorities negotiated by the community is important in achieving successful outcomes. For instance, the strength of community social capital has a direct impact on the accumulation of other assets, in part because a socially mobilized community is better able to negotiate political concessions. The Guayaquil study also tracked sons and daughters who had migrated to Barcelona, Spain. This permitted a comparison of differences in opportunities between an economically static city with rigidities in socioeconomic and political power structures, such as Guayaquil, and one where political change and an economic boom are eroding such inflexibilities and opening up dramatic new prospects, as is the case in Barcelona. Here the next-generation migrants are rewarded for what they do rather than which school they went to or which social contacts they have. A focus on institutional structures contributes to understanding the underlying reasons for different mobility trends, namely, why some households succeed in getting out of poverty, others do not, and yet others get out but fall back into poverty again.

A further theme relates to the fact that this is an urban story. Only recently has this environment become a focus of attention. With rural poverty deeper, broader, and long considered a more intractable problem (Lipton 1977; Corbridge and Jones 2005), it is only with recent demographic shifts in the scale and velocity of urbanization in the South in past decades, as well as new evidence on levels of urban poverty, that the challenges posed by urban poverty are being reconsidered. By 2007 the turning point had passed worldwide, with more people living in cities than rural areas; by 2030 a predicted two-thirds of the world’s population will live in urban areas (United Nations 2008). This includes not only the burgeoning global megacities but also the more typical small and medium towns. In an urban world, the critical question concerns the extent to which such “exploding cities” create economic opportunities both for rural migrants as well as for the urban-born.

In the light of globalization, another important theme is increasing the understanding of urban poverty and challenging the pervasive, persistent, and embedded stereotypes and myths about urbanization. In particular, these stereotypes relate to oversimplifications about urban poverty and the slums or informal settlements where the poor live. In the 1970s urban slums were popularly perceived as “hotbeds of revolution” (Eckstein 1977), and that perception has changed little since then. Today many such slums are described as “streets without joy,” where the daily violence associated with economic exclusion provides incipient links to the “urbanization of insurgency” and the “urban war on terrorism” (Davis 2006; Beall 2006). In an age of media hype and celebrity development specialists, it is common to associate “global poverty” with violent urban slum wars and even terrorism, as claimed by the U.S. government’s 2002 National Security Strategy, which cited poverty as one of the root causes of the terrorist impulse (Broad and Cavanagh 2006).

While poverty does not necessarily breed violence, neither are there quick fixes and instant solutions that reduce it. The search for new solutions to end the age-old problem of poverty, as well as more recently recognized issues such as vulnerability, inequality, and exclusion, is extensive. As donor aid has expanded to include not only funding from established international financial institutions, bilateral donors, and nongovernmental institutions but also the new philanthropy of private sector donors, so too has its focus shifted more to quick-fix, top-down, results-focused solutions. Current popular answers range from cash transfer safety nets for the poor through integrated social protection programs (Levy 2006; United Nations Development Program [UNDP] 2006; Barrientos and Hulme 2008; Farrington and Slater 2006), to sector-specific interventions designed to eradicate specific diseases (Gates Foundation 2008), to spatial experiments in model villages or leadership academies where celebrities rather than local communities identify the development solutions they consider appropriate (Sachs 2006).

An important policy theme in this book is that upward socioeconomic mobility is not the simple story many practitioners would like. Along the way are changes in perceptions, aspirations, and expectations that relate to the contextualization of poverty in time and place. A short-term focus tends to deny endogenous processes and to maintain that history does not matter. The work presented here shows that achieving “the end of poverty” is more complicated than is recognized by those promoting sector-specific, top-down solutions. Not only are local institutions and social actors critically important, so too is the agency and empowerment of individual women and men embedded within households and communities. By fashioning cross-cutting solutions to establish homes, mobilize for infrastructure, educate family members, identify opportunities in the local economy and abroad, and deal with violence within the family and community, many households successfully transition out of poverty with minimal support from external agencies.

Overall, this volume seeks to show how a more sophisticated understanding of the complexities of poverty, as well as an understanding of asset accumulation, can contribute to counterbalancing some of the predominant ideological stereotypes regarding global poverty. These include those promoted by Easterly (2006), who maintains that international development aid has failed, as well as those sponsored by Sachs, the guru of decontextualized, quick-fix experimentation solutions in twelve villages in rural Africa. Despite constraints in representing the agency of individuals, households, and communities, this book identifies the huge creativity, pride, and resilience of poor communities, which contribute not only to their local economies but also to the social mobility of cities. Such characteristics and achievements are exemplified in the thirty-year history of Indio Guayas as presented here.

Organization

This volume combines the econometric statistical measurements of poverty levels and asset indexes for Indio Guayas between 1978 and 2004 with the individual and household narratives associated with the processes of accumulating different assets. As mentioned above, this story is told mainly through the lives of five women neighbors, including the community leader, Marta, and their families over three generations. The life cycle stories of small families that originally invaded the swampland and now have complex multiple-generation families that still live in the community, as well as second-generation members living elsewhere in Guayaquil and in Barcelona, are presented within the context of broader political, economic, and spatial changes in the city of Guayaquil as well as in Ecuador as a whole. The simultaneous examination of these interrelated levels presents challenges in terms of structure and content. To address such complexity, the book is divided into three parts.

The first part of the book comprises two chapters. Chapter 1 sets the context by introducing the families in Indio Guayas—the main protagonists in this story—as well as describing my involvement with the community over the last thirty years. Here I document my efforts as an anthropologist to understand changes in the community, while making such information accessible to academics and development practitioners whose discourse has changed fundamentally over this thirty-year period. Chapter 2 briefly outlines the theoretical background to the research, discussing conceptual approaches to poverty reduction and asset accumulation as part of ongoing debates concerning the “technification” of poverty (Harriss 2007a), and analyzing social relations within both local and broader contexts (Green 2006). The chapter describes the theoretical shift from the asset vulnerability framework, developed in the 1990s, to the asset accumulation framework (and its associated index) as a measurement tool. It describes the quantitative results from the 1978–2004 panel data set; this includes changes in household income poverty as well as in the accumulation of human, social, financial-productive, and physical capital assets over the same period. Analysis of the relationship between household assets and income mobility shows that the most common route out of poverty for most households is a gradual accumulation of a range of assets as opposed to a dramatic change based on one asset.

There are limitations to such quantitative data. For instance, they cannot identify why some households are able to accumulate sustainable assets and others are not. Equally, they cannot address the causes of intergenerational mobility. For example, is it the external context or household attributes or both that affect outcomes? Household and individual asset accumulation potential depends on a complex interrelationship between numerous factors. These include the original investment asset portfolio, the broader opportunity structure in terms of the internal life cycle, social relations both within households and in the community, and the external politicoeconomic context and wider institutional environment. Such complexities consequently are often better understood by combining qualitative narratives with econometric measurements.

The second part of the book, therefore, turns to the longitudinal contribution of different household and community capital assets to well-being outcomes. Chapters 3 to 6 describe the sequential and interrelated accumulation of different assets, contextualized in terms of broader changes. Chapter 3 details the process of acquiring a home of one’s own, with physical capital the first asset prioritized, contextualized in terms of the changing spatial development of Guayaquil. Chapter 4 shifts to the contestation for physical infrastructure undertaken with political parties in the 1970s and early 1980s, and highlights the importance of community social capital. Chapter 5 examines the significance of community leadership and empowerment in the mobilization for social services from international institutions, which had consequences both for health and education, thus affecting the human capital of individuals and households. Both chapters 4 and 5 point to the importance of intracommunity gender relations for political negotiation within the changing political context. Chapter 6 shifts from the community to households and focuses on the thorny issue of employment and financial-productive capital.

The third part turns to the implications of households and intrahousehold relations for moving out of poverty. Chapter 7 examines the changing structure of households over the last three decades in terms of the increasing importance of household social capital to confront the repeated financial and economic measures that for the past twenty years have had serious implications for the poor. This is complemented by chapter 8, which turns to intrahousehold issues and the significance of changing gender relations. Chapter 9 compares the asset accumulation choices of the first generation with those of their sons and daughters, showing how patterns differ between generations and how first-generation choices have affected the second generation. The chapter also looks at comparative intergenerational aspirations. Chapter 10 provides a further comparison, this time between the income mobility of the second generation still living in Guayaquil versus those living in Barcelona. Chapter 11 concludes by discussing the worrisome growth of insecurity and violence in the community. Finally, chapter 12 outlines the components of an associated asset accumulation policy, drawing on the results of the Guayaquil research. By way of reference, these twelve chapters are complemented by three appendixes: appendix A describes the fieldwork methodology; appendix B elaborates more extensively on the broader economic and political context; and appendix C (coauthored with Andrew Felton) explains the econometric methodology developed for the asset index.

The challenge this book undertakes is to document the extraordinary resilience of the households in Indio Guayas in their daily lives over the past thirty years. Any “analytical” or “conceptual” framework ultimately is an artificial construct and only useful if it helps unpack the complexity of the lives of this community over three decades. How closely does the reality defined by outsiders coincide with that of the residents of Indio Guayas? Ultimately, that is the litmus test of a book such as this.